Computer "scientist"

Alex Clemmer is a computer programmer. Other programmers love Alex, excitedly describing him as "employed here" and "the boss's son".

Alex is also a Hacker School alum. Surely they do not at all regret admitting him!

Alex Clemmer is a computer programmer. Other programmers love Alex, excitedly describing him as "employed here" and "the boss's son".

Alex is also a Hacker School alum. Surely they do not at all regret admitting him!

I spent my first few weeks at Hacker School writing a Python compiler from basically scratch.

The task of merely parsing a complete language like Python can be quite intimidating at the outset. I’ve found that many people simply assume it’s nearly impossible.

I began to wonder if it was possible to write a parser so clear that it would seem obvious how the parser worked.

Let’s look at where I took this. (Full source available here.)

This article will go through 3 basic phases:

NOTE: The parser is written in Haskell, but P-L-E-A-S-E do not worry if you don’t know Haskell. I’ve endeavored to make it readable to everyone. Be sure to email me at

clemmer.alexander@gmail.comif you have questions.

The following is a function called fileInput that merely parses a file. (See original source here.)

fileInput = lines <~> endOfFile ==> emitProgram

where lines = lineCfg

endOfFile = ter "ENDMARKER"

I’ve tried to get this to mirror the way I would explain a Python file in English. This is how I’d read it in my head:

A

fileInputis a series oflinesconcatenated with anendOfFilemarker,whereourlinesare defined using a functionlineCfg, andendOfFileis defined using some functionterthat we don’t understand yet. Once we parse a Python file, we call a functionemitProgram, which tells us what to do with the parsed Python source code.

Let’s break down this code.

The <~> operator just means “concatenate”. The expression lines <~> endOfFile basically means “a bunch of lines concatenated with an EOF marker.”

The ==> operator represents a “rule”—simply put, pattern ==> func will call the function func after it finds pattern in the data you’re parsing.

The where keyword just gives us concise English-like syntax for defining and using variables, e.g., “a file is a bunch of lines concatenated with an EOF marker, where lines is defined as $WHATEVER and the EOF marker is defined as $SOMETHING_ELSE.”

The point of ter "ENDMARKER" is to match to the ENDMARKER token, which is a special token indicating that the file has ended. We’ll talk more about these “token” things in the making parsing easy section, but for now just think of it as a signal that the file has ended. If you know about context-free grammars, ter is actually a terminal in the grammar, as opposed to a rule (recall that a rules is defined by the ==> operator).

If you don’t know Python, here’s an example of a Python function. It’s called cowfun, it takes no arguments and returns the string "cow".

def cowfun ():

return "cow"

The following code (original source here) parses arbitrary function definitions.

funcdef = def <~> id <~> parameters <~> colon <~> body ==> emitFuncdef

where def = ter "def"

id = ter "ID"

colon = ter ":"

body = suite

In English I would read this as:

A function is the keyword

defconcatenated with the function’sid(or the name of the function, which in this case iscowfun), a list ofparameters, acolon, and abody. When we parse a function, we will callemitFuncdef.

There’s nothing really conceptually new in this example. <~> still means concatenation, and the components like def and colon are defined in the where block.

The ter function is used here in ways that might be sort of new, however. ter "def" basically matches the keyword def. ter ":" matches a colon in the source. ter "ID" matches an identifier—in this case, the token stores both the fact that it’s an ID token, and the identifier itself, which is cowfun in the example above.

suite is another rule contained elsewhere in the source.

raise fromIn Python, exceptions are thrown using the raise keyword, e.g., raise CowError.

It is possible to “cast” one exception to another type using the raise from syntax. For example, here we raise a CowError and then “convert” it to DifferentError using the raise from syntax.

except CowError as ce:

raise DifferentError from ce

Here is the code (source) for parsing this syntax:

-- eg, `raise ValueError from msg`

raiseFrom = fromNowhere

<|> from <~> test ==> emitFromStmt

where fromNowhere = eps ""

from = ter "from"

The <|> operator is new. It’s read as “or”. So in, English:

Either we’re using

raise fromsyntax, or we are not.

Note that the precedence rules are important here. The desired behavior is to be able to chain together a lot of ==> rules, e.g.,

aCow = isGreen ==> milkGreenCow

<|> isPurple ==> milkPurpleCow

<|> isWhite <~> isBlack ==> milkCheckeredCow

In order for this to behave as we want, the precedence rules should group together the expressions in the following way:

aCow = (isGreen ==> milkGreenCow)

<|> (isPurple ==> milkPurpleCow)

<|> (isWhite <~> isBlack ==> milkCheckeredCow)

This means that the <|> operator should have lower precedence than both the <~> and the ==> operators. In other words, the very last thing to get evaluated should be the <|>.

And indeed this is how the parsing library we’re using works.

Aside from that, the new expression eps "" matches “no token”, or more liberally, “nothing”. If you know about CFGs, this is the equivalent of epsilon. It is basically saying “there’s no from” clause.

The expression ter "from" just matches the keyword from.

The rules we’ve constructed with operators like <|>, <~>, and ==> formally describe all possible Python programs. (Well, technically we’re parsing a large subset of Python, but you get the point.)

In other words, they describe what a Python program is.

The question remains: how do you use these nice descriptions of different Python constructs to actually parse Python?

The full answer of how parsing algorithms work is a bit outside the scope of this post, but the short answer is that we’re using a Haskell library called Text.Derp, which defines the <~>, <|>, and ==> operators, and is responsible for turning rules like the ones we’ve defined above into code that will actually parse source.

(I experimented with many parsing libraries and ended up choosing Haskell’s Text.Derp library because it simply resulted in the cleanest code. If you’re curious why, one reason is that Text.Derp works by parsing with derivatives (talk, paper). But it also happens to be a well-designed library.)

The code that actually does the parsing is below (source here).

main = do code <- (hGetContents stdin)

let res = toList $ Parser.parseFile $ Lexer.lex code

case res of

[] -> putStrLn "#f"

x -> showNL x

This is the main routine of the parser. It takes data in from standard in, and assumes that the code it gets represents a complete Python file. It calls the lexer using Lexer.lex (more on the lexer in a minute) and then parses the tokenized output using Parser.parseFile.

The critical part is the case statement. If the parser outputs [] (the empty list), then the parse has failed, and we output #f. Otherwise we output the parsed file. (More on that in a minute too.) Note that this isn’t a bug—even an empty program should have output, and I encourage you to try it to see why using the shell command in the next section.

At this point, we have a bunch of clean rules that tell us what a Python program is, and we have code that takes those rules and applies them to actually parse Python source.

One question lingers: what is the parser actually doing?

A parser’s job, vaguely, is to take unstructured stuff and turn it into structured stuff. In this case, we take in a string representing the contents of a Python file, and output a structure called an abstract syntax tree, or AST.

The idea behind constructing an AST is to represent a program as a tree, which (hopefully) makes program execution a fancy tree walk.

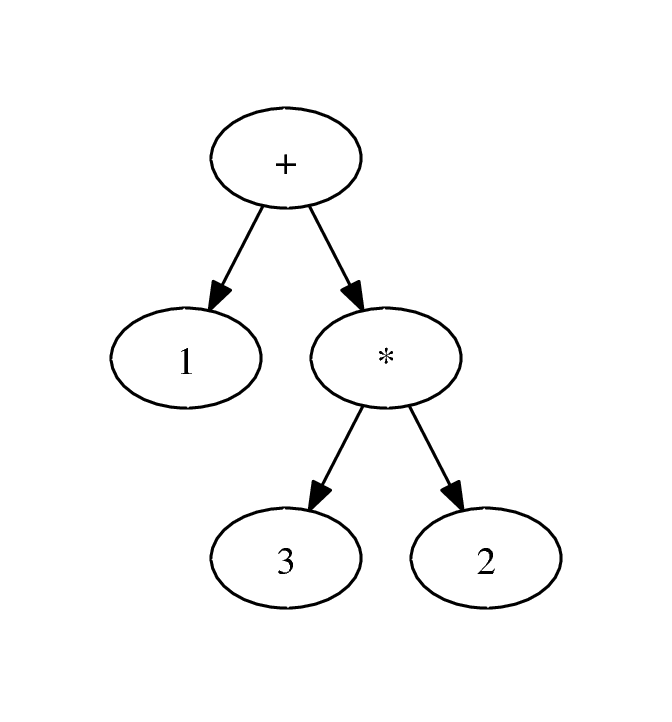

For example, consider the expression 1 + 3 * 2. According to order of operations, we want to evaluate this as 1 + (3 * 2). We can represent this as a tree:

Since the multiplication is a child of the addition, to perform addition, we must first obtain the result from the multiplication. Hence, evaluation is a function of the tree traversal.

In Python, all valid programs can be represented as trees of syntax much like this one, except the nodes can be any statement or expression, not just numbers and operators. For example, a while statement will have a predicate and a body, which can itself contain more while statements.

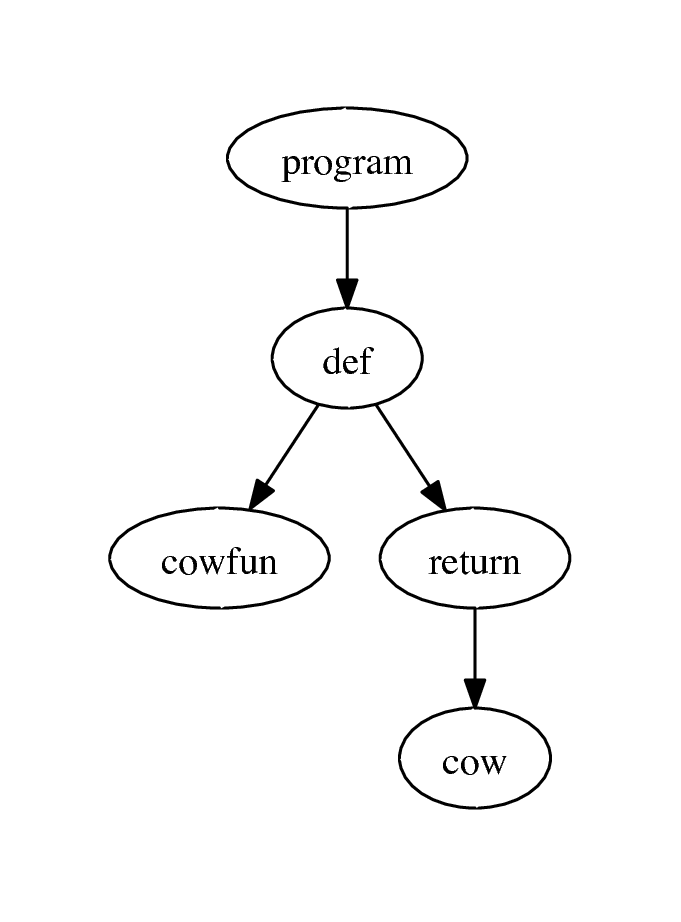

As a concrete example, let’s look at the AST for the very short Python program def cowfun(): return 'cow' that we saw earlier.

> echo "def cowfun(): return 'cow'" | make pyli

'(program

(def

(cowfun)

((return

"cow"))))

The command at the top of this code snippet runs this small program through the parser in my lexing/parsing suite, whose source I’ve been showing you this whole time.

The resulting tree is represented as a LISPy list of lists. Here we see that def is a child of program. Similarly, the name cowfun and the return statement are children of def. The LISPy AST is the ultimate output of the parsing functions I showed you earlier. You specify the rules of Python, then you run the parse using functions from the parsing library, and what you get out is an AST.

If you don’t do well with fancy LISPy trees, we can vizualize it using the dot command from the Graphviz suite.

From here you can do all sorts of things. You can evaluate and run the code. You can optimize the code by transforming the tree. You can make a Python-to-X (where X is C++ or something) compiler by transforming the code into an AST for a different language and doing an inorder traversal that emits the code in a target language.

And so on.

It turns out that the code I wrote is relatively simple because of a phase called lexing.

During the lexing step, we take the Python source and break it down into a series of tokens—we take the raw text and break it into keywords, ids, number literals, string literals, and so on.

The reason we do this is to simplify the parser. By breaking it down into a series of such tokens, the parser’s job is simply to deterimine whether the order of the tokens makes sense. If we didn’t have the tokenized representation, it would have to figure out that something is, e.g., a keyword, and then figure out if that makes sense in the context in which it occurred.

This is possible, but much more annoying to write.

Here’s an example using our simple program from before, def cowfun(): return 'cow'. We’ll plug it into the lexer (from my lexing/parsing suite) via standard in. In response, we receive a set of tokens as output.

> echo "def cowfun(): return 'cow'" | make pyle

(KEYWORD def)

(ID "cowfun")

(PUNCT "(")

(PUNCT ")")

(PUNCT ":")

(KEYWORD return)

(LIT "cow")

(NEWLINE)

(ENDMARKER)

The only reason to tokenize before parsing is because it greatly simplifies parsing. Now the parser’s job is to make sure that the id cowfun makes sense coming after the keyword def.

If the lexer step didn’t exist, it would have to figure out that def was a keyword, then that cowfun was an id, and then finally whether they make sense to appear in that order.

The moral of the story is: lexing makes parsing easier.

While I can’t impart all of parsing Python onto you in this short post, I hope that I have convinced you that you can understand the source code of this parser if you want to.

It is not a black art.

It is simply a matter of reading the code and (maybe) asking questions. To me or the program.

For the future, I would propose the following.

If you enjoyed this post, you should consider applying to Hacker School. The space is full of some of the nicest, smartest hackers I have ever met. Working around them has been a joy and an inspiration. Their thoughtful feedback and enthusiasm gave me the energy and the tools I needed to be able to approach the work you see here.

Finally, a big thank you to David Albert, Scott Feeney, and Martin Törnwall for reviewing preliminary versions of this article.