Computer "scientist"

Alex Clemmer is a computer programmer. Other programmers love Alex, excitedly describing him as "employed here" and "the boss's son".

Alex is also a Hacker School alum. Surely they do not at all regret admitting him!

Alex Clemmer is a computer programmer. Other programmers love Alex, excitedly describing him as "employed here" and "the boss's son".

Alex is also a Hacker School alum. Surely they do not at all regret admitting him!

[Translation available in Japanese]

So you want to learn OCaml. Where do you start? What do you do?

I’ve been an OCaml beginner probably a dozen times — picking it up, dropping it, and picking it up again so many times I’ve lost count.

This time it’s stuck, and I think it’s because the community has fundamentally changed.

Here’s what worked for me.

Read Real World OCaml (colloquially: RWO), and accept no substitutes. It might be the best computer language book I’ve ever read in my life.

In addition, I would advise against reading other books, as they tend to be incorrect and/or in French.

(EDIT: a commenter points out that OCaml from the Very Beginning doesn’t suck, and is more beginner-oriented. I’ve never read it, but Ron Minksy says nice things about it. So there’s a data point.)

Here are some nice things about RWO.

for loop”), and the core

library (e.g., “call this to get a List<T>), and give you no

other context.OCaml has a very strong type system. A combination of this fact, plus the fact that the types are usually inferred (i.e., they are usually not written down explicitly), makes OCaml a language where your intuition about what should be correct will be regularly shot down, and then shoved in your face until you get it right.

Please.

Please, please make this easy on yourself.

Invest in tooling that will shorten the gap between writing something and the compiler telling you it’s totally wrong.

Follow the RWO installation instructions to the end. In particular:

Since it takes time and energy to invest in tooling, I’ll try to entice you by showing you some stuff that’s cool that you can do with them.

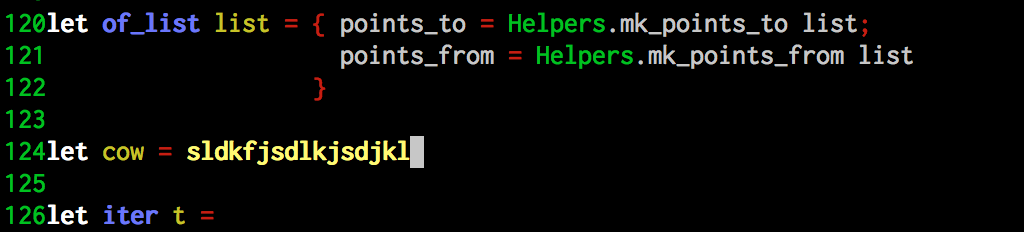

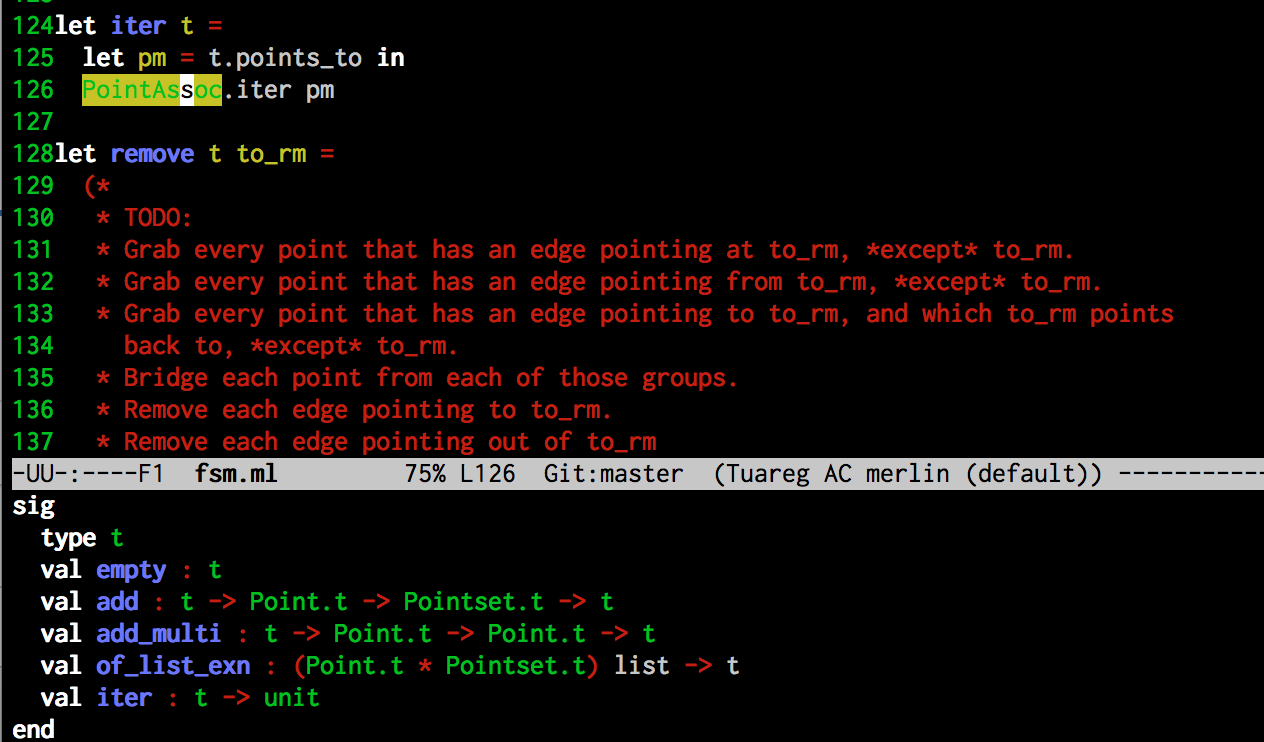

Files are compiled on save, which means that things that don’t compile are highlighted in yellow:

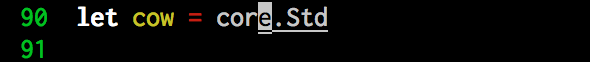

As you type, Merlin will produce a list of autocomplete suggestions:

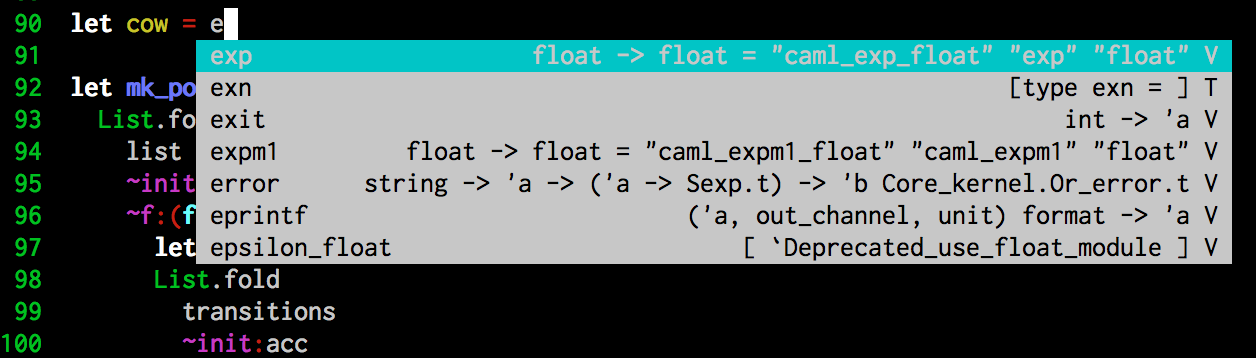

Merlin also has a hotkey (on emacs it’s C-c <TAB>) that will bring up a list of suggested autocompletes:

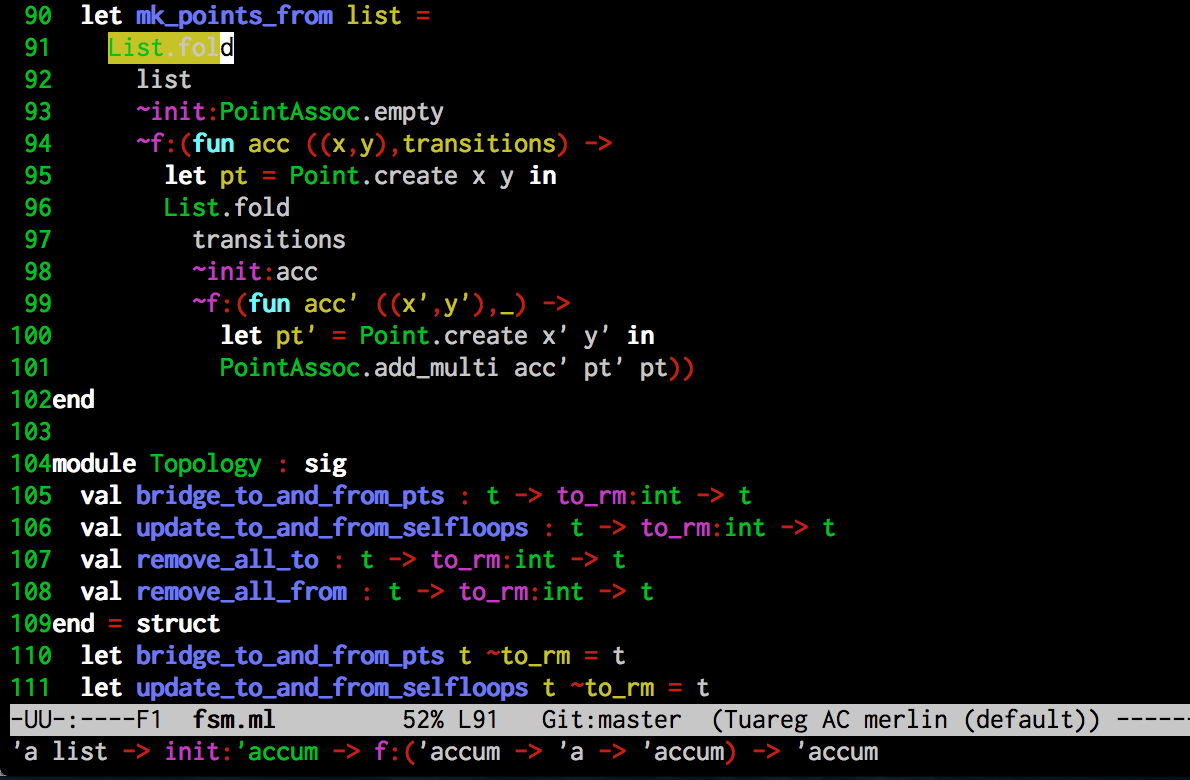

Another hotkey (on emacs it’s C-c C-t) takes the expression that the cursor is currently at and tells you what type it is!!! (It’s included at the bottom of the screen.) This is incredibly convenient because the compiler then doesn’t have an opportunity to complain about types.

If you press this same key combo on an expression that is a type, it simply brings up the type definition!!

There are a lot of things you can do here. This is just a taste. It’s an optional thing, but really, it’s well worth the time savings.

Good question! It’s important to see really skilled programmers use OCaml in a really idiomatic way!

The best open OCaml system is probably the Jane Street Core and the Jane Street Core Kernel. For example, here is their map implementation, which is very good.

The source for utop and anything coming out of OCaml Labs is good, but unfortunately, good open source OCaml projects are still somewhat hard to come by in general. Eventually this will probably change.

The standard OCaml tutorials are now awesome. They used to be non-existent, then they were terrible. Now they are awesome.

The 99 OCaml problems exercise is ok. It might not be the best way to learn, depending on your background, but I found it to be a useful way to learn common manipulations for standard OCaml data structures. In particular, I found that writing something, and then looking at the solution, showed me where I was not using idiomatic OCaml. That was helpful.

There are both contained on the the official OCaml “learn” page . It’s a pretty good resource to start, and it will be consistently updated in the future.

A good start is the documentation for Core.Std. This explains the standard data structures of the Jane Street Core, which is a good place to start.

To get started with that, it may be necessary to look through the relevant online RWO chapters. (Certainly this was true for me.)

I have friends who I talk to. I hear IRC is good, and I hear there are mailing lists. Personally I don’t use either.

Everyone’s path varies, but personally I had the most luck with the following.

I guess I don’t really have anything to say in parting, other than that if you have comments about what does/does not work, I’d be happy to hear them.