Computer "scientist"

Alex Clemmer is a computer programmer. Other programmers love Alex, excitedly describing him as "employed here" and "the boss's son".

Alex is also a Hacker School alum. Surely they do not at all regret admitting him!

Alex Clemmer is a computer programmer. Other programmers love Alex, excitedly describing him as "employed here" and "the boss's son".

Alex is also a Hacker School alum. Surely they do not at all regret admitting him!

The performance of live site systems — everything from K/V stores to lock servers — is still measured principally in latency and throughput.

Server I/O performance still matters here. It is impossible to do well on either of these metrics without a performant I/O subsystem.

Oddly, while the last 10 years have seen remarkable improvements in the I/O performance of commodity hardware, we have not seen a dramatic uptick in system I/O performance. And so it is worth wondering: are standard commodity OSs even equipped to deliver these I/O improvements?

This is the central question behind the recent OSDI paper by Simon Peter et al.

Perhaps the most interesting things I learned from the paper is that the answer is actually no: today, the main impediment to I/O latency seems to be the OS kernel itself.

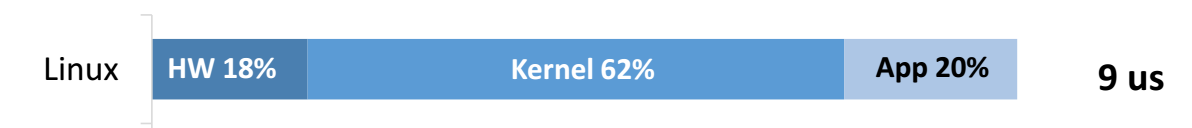

In one striking experiment, they take commodity linux and attempt to break down the latency of a simple read and a simple write in Redis on commodity hardware.

(NB, the “latency” part of this is important — as I’ll mention in a minute. It is possible to improve throughput by using multiple threads, but the point is that there is still room for improvement in the latency of a particular request, especially at the level of a datacenter, where this sort of thing is potentially worth a lot of money.)

In particular:

The results are striking:

Read (in-memory):

Write (persistent data structure):

Worth pointing out is that in each case about 70% of the time in the kernel is spent in the networking stack. Even with larger payloads, these numbers should also remain a fairly constant overhead, since the networking stack has to be re-invoked for each packet. That said, if the application is more expensive than just writing the packet to memory, then the application time might balloon. But the network time consumption will remain about the same.

One of the interesting things to me (though I am a networking/OSs noob) is the deliberate choice to use single-threaded latency, rather than throughput, as the core measurement.

Notice that, with the latency numbers, the cost of the kernel is explicit and noticable. But with throughput, and with multiple threads, it would be possible to forget that the kernel exists — we could easily have measured only an increase in queries per second, and completely missed the fact that each query spends 84% of its time in the kernel.

This sort of purposeful approach is important: it’s hard to optimize what you don’t measure.

Understanding roughly how much time a request will spend in the kernel is generally useful for designing and maintaining scale web services.

Up to this point, our main weapons against latency have been things like pipelining and multithreading. It is interesting to think what might happen, though, if the latency less of an issue. For example, it makes me (a networking noob) wonder whether things like the pipelining stack in SPDY might be simpler.

In any event, the rest of the paper explores how we might go about reducing such latency, using this experiment as motivation for a research OS called Arrakis.

The core idea of Arrakis, as far as I can tell, is that many of the things the kernel provides for I/O can actually be provided by commodity hardware — for example, protection, multiplexing, and scheduling.

In other words, it looks like the goal of Arrakis is to pull the I/O out of the “control plane” (i.e. to pull as much of it out of the kernel as possible), and to put it into the userspace “data plane” (i.e., such that things like multiplexing happen directly on the hardware, but never in the kernel).

The results look good, too — the authors claim 81% reduction in write latency, and 65% reduction in read latency.

Still, exciting though it is, there seems to be room for improvement. For example, having an OS that requires manual configuration for specific hardware, especially at the level of the datacenter, seems like it might be bad. The vast majority of service-level outages are still caused by configuration errors, and making them more opaque is not a favor.

I suppose time will tell whether this fear is founded in reality or not — I’m still more or less a complete OS noob, in any event.